Adapting Bernhard Schlink's Holocaust novel The Reader for the big screen was always going to be a challenge, but the deaths of two producers - Anthony Minghella and Sydney Pollack - made it all the harder. David Hare, who wrote the screenplay, recounts the tortured journey from book to film

- The Guardian, Saturday 13 December 2008

- Article history

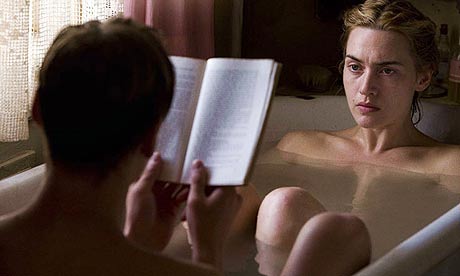

Not a book about forgiveness ... The Reader

Long before film-makers of any nationality began their attempts to offer fictionalised drama about the Holocaust, the Swiss director Jean-Luc Godard made a famous statement: "If ever a film is to be made about Auschwitz, it will have to be from the point of view of the guards."

- The Reader

- Release: 2008

- Countries: Rest of the world, USA

- Cert (UK): 15

- Runtime: 123 mins

- Directors: Stephen Daldry

- Cast: David Kross, Jeanette Hain, Kate Winslet, Ralph Fiennes, Susanne Lothar

- I would love to be able to claim that Godard's remark came immediately to mind when I first read Bernhard Schlink's novel The Reader on its original publication in the English language in 1997. If it had, it would most certainly have been appropriate. Like so many people in Britain, I had first heard of the book when I read George Steiner's recommendation in the Observer: "A masterly work . . . The reviewer's sole and privileged function is to say as loudly as he is able, 'Read this' and 'Read it again.'" Since nobody had ever imagined Steiner was a critic who would praise any modern novel lightly, this ringing endorsement was especially striking. I went out and bought the book at once.

- The reason The Reader made such a strong impression and became such a success throughout the world was because it genuinely did open a new field of inquiry. It had already taken a long time for the suffering of Jews in the European concentration camps of the 1930s and 40s to reach deep into public consciousness. In the 20 years immediately after the end of the war, there was an understandable reluctance among survivors to describe in any detail what they had been through. It was as if a seemly reticence were the only available response to murder on such a previously unimagined scale. In Israel, in particular, the resolve to build a new country meant that older people were not encouraged to talk about the past. Often, indeed, people felt ashamed of being alive when so many of their families and fellow inmates had been killed. When Primo Levi's If This is a Man was first published soon after the war, most of the 2,500 copies printed mouldered unsold in an Italian warehouse.

- If in Israel it was the appearance and conviction of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961 that brought about a decisive shift in public understanding, the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt between 1963 and 1965 - realised through the persistence of one lone prosecutor, Fritz Bauer - had a comparable impact in Germany. Thirty years after those trials, it was Schlink's singular achievement as a lawyer conceiving his first non-detective novel to invent a narrative that finally articulated the dilemma of so many Germans who were born, through no fault of their own, as the children of a great crime. How does a succeeding generation deal with the transgressions of their parents? How do they find a way of living anything like a normal life? The Reader is not simply a novel specific to the postwar German experience. It is also a more far-reaching exploration of the painful and difficult process we all now know under the name of truth and reconciliation.

- The story of The Reader is simple on the page, conceived, it seems, with the clarity of the fable, reminiscent as Steiner says "of an extended novella in the manner of Kleist or Schnitzler". But once examined, its meanings become more complex. In a German provincial town in the mid-1950s, a 15-year-old boy, Michael Berg, is given a sexual initiation by an older woman, Hanna Schmitz, whom he has met when he has fallen ill on the way home and to whom he reads aloud great works of world literature. Even at the time and with so little experience, Michael, out of his depth, can nevertheless feel that the relationship has an undertow which is not wholly usual. Without warning, Hanna disappears from his life. Some years later, when, as an undergraduate studying law, Michael attends a war crimes trial in a town near Heidelberg, he is shocked to discover that one of the defendants is his one-time lover. Hanna has worked as a guard in a concentration camp. On the subsequent death marches, she has committed a shocking war crime. But disturbingly, as the trial proceeds, Michael realises he is in possession of evidence about her that, if he were to reveal it, would serve at least to mitigate Hanna's sentence. Can he bring himself to help someone whom he has loved but who he feels has betrayed him? Worse, what duty does he have towards someone who has done so many terrible things?

- It's clear the moment you finish the novel that in no sense can it be seen as a book about forgiveness. On the contrary, Schlink makes it plain, both in his writing and in private conversation, that no writer of whatever background, portraying the crimes of the German people, has the moral right to extend to his characters any possibility of redemption. For that reason, anyone whose unlikely response to the book is to want to make a film of it faces an unusual challenge. The conventional Hollywood narrative always ends in the hero coming to some understanding of his own flaws. Uplift, you may say, is built into the contract. But Hanna, at the author's own insistence, reaches no real understanding of what she has done. You may even argue that no understanding of such extreme crimes is even possible. How, then, was anyone to embark on a movie in which one of the two principal characters essentially learns nothing?

- Perhaps it was a mark of my stubbornness that I wanted to write the screenplay of The Reader precisely because I knew the task would be so unusual. More charitably, you could say that even by the time I read the book 10 years ago, I was already, like so many contemporary cinemagoers, weary of genre pictures. Much as I still loved going to the cinema, I could no longer endure films that followed formulae the audience already recognised. For me, Schindler's List had represented a high-water mark. I saw it once and never saw it again, because it achieved so completely what Godard had thought unachievable. It did justice to the sufferings of its subjects. It was both unnecessary and impossible to attempt to do it better. What excited me was the prospect of attempting its opposite. We would try to examine the consequences of the same events, but from the point of view of the perpetrators and of their descendants.

- It isn't possible in the course of a short article to get across just how tortured the path has been from reading the novel to finally sitting in front of a fresh-struck print of the film. All films are hard, but this one was harder than most and, as it turned out, crueller. The rights to the book had been sold on publication to the British film-maker Anthony Minghella, and to his American partner Sydney Pollack, who together had formed a benign organisation called Mirage, which existed both to offer companionable help to fellow film-makers, and for Sydney and Anthony to develop their own projects. However much I badgered Anthony to be allowed to write the screenplay, it was his firm intention to write and direct the film himself. It was nine years later, in the autumn of 2006, that Anthony finally rang the director Stephen Daldry to admit defeat. He would never be able to find time among his numerous commitments to get round to The Reader. He felt bad that he had not been able to fulfil his promise to the author of the book to make the film. So Stephen and I would therefore be allowed to go ahead, but on one condition. We must deliver the film within one calendar year of being granted the rights.

- No one at that point could have foreseen the extraordinary series of misfortunes that soon overtook us. Some time after the start of filming, we lost our original leading lady, happily to pregnancy. So the shoot was first delayed and then suspended. During this hiatus, we worked again with Sydney and Anthony, two producers who made an interesting contrast - Anthony discursive, generous, professorial, like a popular teacher at a good university; Sydney quieter, more decisive, everyone's favourite acting coach, keen always to address the fundamental themes that on close examination can make Schlink's writing seem so mysterious. Time and again, Sydney would draw us back to the question: What exactly is the metaphor of reading in the film? What is the function of literature?

- During these relaxed meetings we talked with a collegiate ease that, in my experience, is pretty rare in modern Hollywood. Never once did Stephen and I feel we were working "for" Sydney and Anthony. Rather, we were four collaborators on a film that fascinated us equally. So it was a loss beyond measure when both our producers died in the space of two months. We had long known Sydney was ill, dealing with cancer with characteristic grace and dispatch. But Anthony's death was out of the blue. I'd just sent him a scene I'd rewritten. I'd got his reply. A few days later he was dead. He was 54.

- In the middle of these tragedies, somehow the film got made. There were two factors working in its favour. First, there was the skill and resilience of Stephen Daldry, on to whose shoulders the burden of the film at once fell. But second, and just as important, there was the steadfast excellence of the largely German cast and crew, led by Kate Winslet and Ralph Fiennes, and spotted with some of the greatest actors from the German theatre. At the outset, Stephen and I had felt like interlopers, daring to arrive in Berlin to address a subject that, you might think, our hosts knew far more intimately than we. The scrupulousness of Stephen's historical research and the accuracy of his reconstructions were more than a defensive gesture from a film-maker with a professional pride in getting things right. More, it was a group effort from all the Germans who worked alongside us. In every department, the crew were determined not just that this story should be told, but that it should, in every detail, be authentic and convincing. Never before have I felt that the making of a film and the subject of a film - truth and reconciliation - could be so perfectly aligned.

No comments:

Post a Comment